Machine Learning Governance in Tax

Many areas of tax incorporated machine learning, but it is not a silver bullet. What are the potential risks of adopting a machine learning approach to replace manual efforts, and how could we mitigate such risks? This blog post discusses some governance measures I put in place to address these questions.

Common applications

The most frequent machine learning application I came across in tax falls into the category of classification prediction modelling. It typically includes:

- Binary classification - e.g., in direct tax, we look at an expense description to determine its tax deductibility;

- Multi-class classification - e.g., in indirect tax, we look at attributes of a transaction such as ship to, ship from country, goods material, vendor VAT registration, etc. to determine the correct VAT rate applicable.

- Imbalanced classification - e.g., for customs purposes, companies need to classify HS codes for traded goods they send internationally - here we often have very imbalanced data given a specific country product portfolio.

Potential risks

The data we use for training these machine learning models are structured data from historical records. An inherent risk associated with the supervised learning approach is poor quality training data. Nonetheless, even a carefully constructed model with good historic data could lead to model decay (i.e. deterioration of model performance, with lower accuracy). Broadly, there are two types of risks inherent to this approach – 1) data drift or 2) concept drift.

- Data drift refers to when data evolves with time. It potentially introduces a previously unseen variety of data and new categories required thereof. It may also mean a different distribution of data compared to previously used data, which will impact the relevant statistical model used. But there is no impact on previously labelled data. This is likely when our business gradually changes on the raw material purchase or portfolio change over time.

- Concept drift refers to when our interpretation of the data changes with time, even while the general distribution of the data does not. This causes the end-user to interpret the model predictions as having deteriorated over time for the same/similar data. This may happen when there’s a change in relevant legislation or in our determination of how one particular tax code should be assigned.

In addition to the above-mentioned risks, tax has its own embedded risk. In particular, all tax returns are subject to audit by local tax authorities. A tax audit can be traced back many years. Mistakes resulting from machine learning models may happen without appropriate checks or detection by the end-users, i.e. our tax professionals. Relevant governance, therefore, is vital to ensure we have a robust defence when it comes to tax audits.

Governance measures

Based on the risk analyses, I implemented a series of measures to improve the governance for all machine learning classification models implemented in tax:

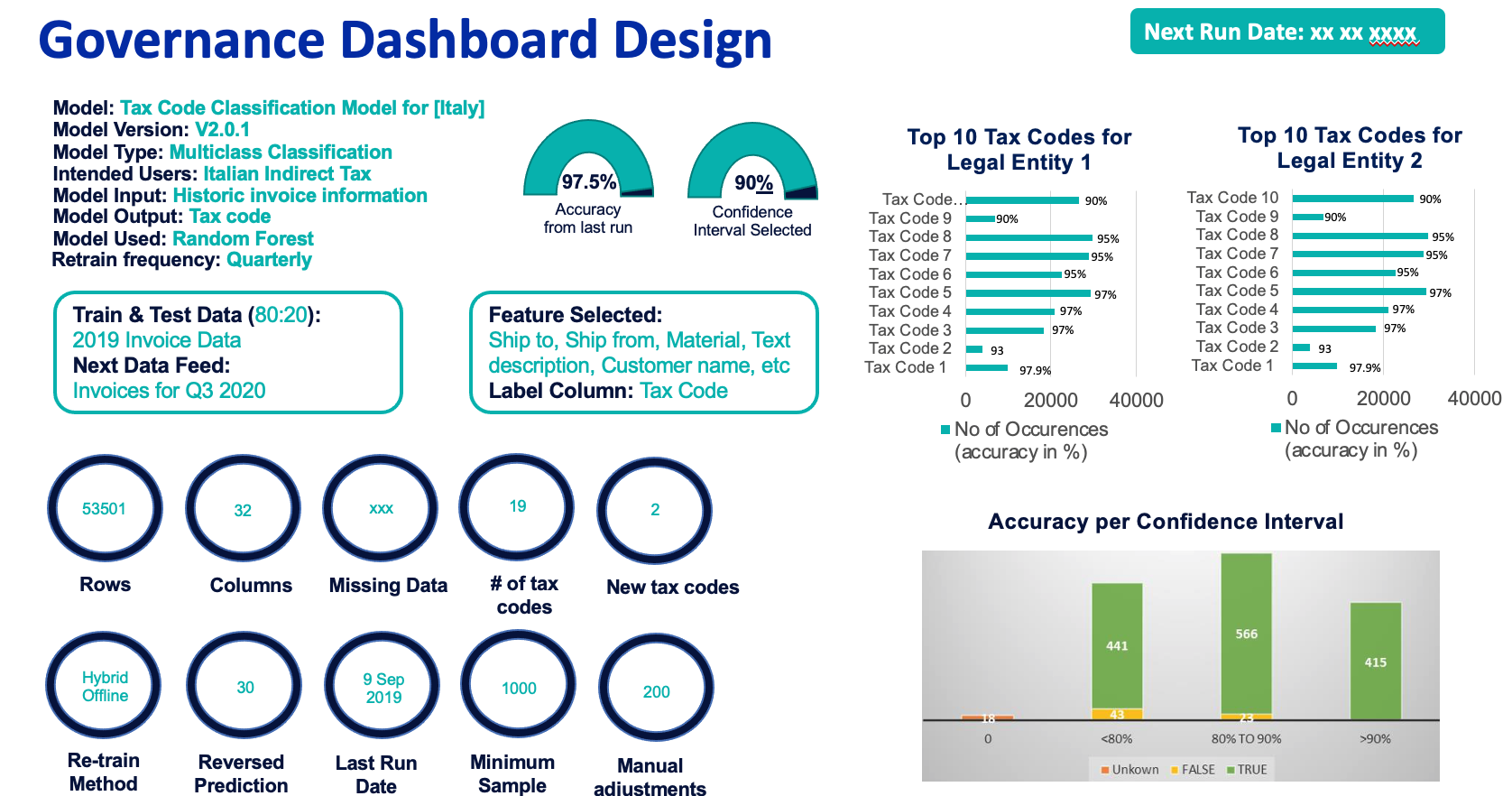

- Build in a monitoring dashboard that has the basic information summarising the models used, performance metrics, and distribution of classification results in terms of how much is done using machine learning vs. rule-based logic, trend analysis and levels of confidence which indicate how much manual work is required. An example of such a dashboard is shown below:

- Written documentation on the solution provided. Adequate training of our tax professionals to understand the methodology being used on a high level, and the meaning of the components in the monitoring dashboard. The training should also allow the tax professionals to be aware of when to intervene manually, assess risks and/or enquire for more details from the solution provider.

- The model used should be refreshed and manually checked periodically, such as on a quarterly or bi-annual basis, using recent training and testing data. This is to ensure the models are indeed performing at the accuracy level we expected and to mitigate the risk of concept and model drifts without monitoring.

- In the long run, the checks and refreshes of the model should be built into the codebase or using a publicly available machine learning model governance package to ensure automated governance is in place without the need for step 3).

Conclusion

As machine learning increasingly integrates into tax processes with wide-ranging consequences, from computer vision for invoice processing to natural language processing for audit text analytics, there is a need for models to be transparent, unbiased, traceable and robust. There are no widely adopted standard approaches to ensure that models meet these requirements. Tax professionals need to be vigilant and prepared to answer questions from future tax audits on tax work prepared by machine learning models.